Symptoms, etiology and therapy of anxiety disorders

The following article provides an introductory and hopefully easy-to-understand overview of the main symptoms, potential causes and, in particular, effective treatment and therapy options of the various anxiety disorders.

The fear reaction, which is based on evolutionary biology, is necessary or even necessary for survival in real dangerous situations – fear reactions in risk-free and danger-free situations, however, are very stressful for those affected and can become chronic.

A common feature of the various anxiety disorders is the strong tendency to avoidance behavior, which can, however, be unlearned by gradually confronting potentially anxiety-provoking situations, objects and/or encounters again. As a rule, such gradual confrontation requires professional psychological-therapeutic support – as a liberating help to self-help that (re)increases the quality of life.

Initially supportive talking therapy, therapy-guided exercises for stress reduction, relaxation and mindfulness-based meditation, as well as exposures within the framework of cognitive behavioral therapy are effective means for successfully and significantly reducing or even eliminating the anxiety problem. Above all, exposure to and confrontation with anxiety-provoking stimuli and/or situations also initially require a measure of overcoming and courage. To break the fear cycle and the often given “fear of fear”.

-

Characterization, forms and symptoms of anxiety disorders.

Anxiety, like sadness and joy, belongs to normal feelings or emotions and represents a necessary part of human experience. In objectively dangerous situations, fear has a warning, protection and action function – we all know this from road traffic, for example. We speak of pathological fear when fear reactions – with their physical and psychological processes – occur without any real apparent risk and danger correspondence. Since there is no need for anxiety symptoms here, they are experienced by those affected as disturbing, inhibiting, very unpleasant and oppressive, which causes considerable suffering.

Due to the stress or anxiety reaction, energies are activated in a flash, which are needed for a fight or flight reaction – useful in case of real danger but stressful in case of anxiety disorders. The sympathetic nervous system activates vegetative processes such as an increase in blood pressure and heart rate as well as increased sweating.

Anxiety can manifest and show itself in different forms:

- Undirected, so-called free-floating anxiety as occurs in generalized anxiety disorder: a persistent fear affecting many areas of life that is not limited to specific objects, situations, or encounters.

- Directed, so-called phobic anxiety: the fear is of specific objects or animals, as in the common spider phobia (arachnophobia), or it occurs in specific situations that are not dangerous by nature (e.g., social encounters).

- Seizure-like anxiety, so-called panic attacks: Sudden and usually “out of the blue” extreme anxiety with severe somatic and psychological symptoms.

In the following, the corresponding anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, i.e. their description and classification according to the main symptoms, are presented in their main features.

1.1 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by persistent, unrealistic or exaggerated fear or worry. In all cases, these worries and fears affect several areas of life, such as work, finances, circle of friends, and partnership or marriage. Sufferers have difficulty controlling the constant and disproportionate worries. In the course of the worry chains, long and senseless brooding often occurs, which is also characteristic of (comorbid) depression.

The anxiety and worry are accompanied by a variety of symptoms that include restlessness, easy fatigability, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep problems.

Common physical (somatic or autonomic) symptoms include accelerated heartbeat (tachycardia), sweating, fine or coarse tremor, and dry mouth, which is not the result of medication. In addition, there may be nausea and paraesthesia in the thoracic region.

The main psychological symptoms in generalized anxiety disorder include feelings of anxiety as well as feelings of dizziness, uncertainty, and lightheadedness.

The clinical psychological diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder requires the presence of a minimum number of specific symptoms over a period of at least six months.

1.2 Social phobia

Social phobia is characterized by a persistent, unreasonable fear and avoidance of situations in which sufferers come into contact with other people and are thus exposed to possible evaluation in the broadest sense.

People who suffer from a social phobia anticipate and fear, in particular, negative evaluation by others; they fear failure, ridicule, or humiliation because of their perceived inept behavior. Social phobias can be narrowly circumscribed (e.g., fear of public speaking or performing) or include much of interpersonal activity (e.g., eating in a restaurant). Typically, individuals exhibit severe anticipatory anxiety when faced with a social situation. As a result of frequent avoidance behavior, social phobia can become chronic and intensified, i.e., an increasing “fear of anxiety” develops in social situations and interpersonal encounters. The vegetative and psychological symptoms occurring in “critical” social situations correspond to those of the generalized anxiety disorder described above.

1.3 Specific phobias

A specific phobia characterizes the persistent, unreasonable and intense fear and avoidance of specific objects and situations. Excluded from this are fear of social functions ( social phobia) and fear of sudden anxiety attacks ( panic disorder).

The most common phobias relate to animals (e.g., spiders, snakes, and dogs), confined spaces, heights, airplanes, and the sight of blood, injuries, and syringes. Also common is a fear of natural environmental phenomena (e.g., thunderstorms) and of specific places and situations (e.g., public transportation, tunnels, bridges, and elevators).

For those affected, these widespread fears have such severe physical and psychological symptomatology that they significantly interfere with normal living and cause pronounced distress. The symptoms felt when confronted with the phobia-triggering objects or situations correspond to those of the generalized anxiety disorder outlined above and those of the panic disorder highlighted below (but with less intensity). As will be shown in the Treatment and Therapy section, the learned phobias can be unlearned or “overlearned,” particularly by desensitization followed by gradually increasing exposure and confrontation.

1.4 Agoraphobia

Originally, the term agoraphobia was understood to mean only the fear of “open places“. However, the scope of the term was expanded and agoraphobia now includes, in addition to the fear of open spaces, the fear of or in crowds, and of situations and places that are experienced as threatening because they cannot be left immediately, such as theaters, cinemas, elevators or subways. Finally, the fear of traveling alone or the fear of traveling far from home also falls under the broader concept of agoraphobia. The key symptom of agoraphobia is the fear due to the lack of an immediately available escape route, which then explains the strong avoidance behavior in front of the mentioned places and situations.

A differentiation is made between agoraphobia without indication of a panic disorder and agoraphobia with indication of a panic disorder.

1.5 Panic disorder

Essential features of panic disorder are frequent anxiety or panic attacks or the persistent worry about such attacks (fear of anxiety). Panic attacks are sudden states of intense fear or discomfort accompanied by a variety of physical (vegetative) and psychological symptoms, which in severe cases include feelings of annihilation and fear of death. Such intense panic attacks last on average about 20 minutes and then slowly subside.

The main vegetative symptoms include palpitations (tachycardia), lightheadedness or “dizziness,” shortness of breath, gastrointestinal distress, sweating, trembling, chest pain, and severe anxiety, which in severe cases can lead to fear of dying. Psychological symptoms include fear of losing control or going “crazy.”

A diagnosis of panic disorder requires that at least one of the attacks be followed by at least one month of persistent apprehension about the occurrence of further panic attacks or worry about the meaning of the attack or its consequences. Feared consequences specifically include fears of losing control or suffering a heart attack.

The majority of anxiety attacks occur unexpectedly “out of the blue,” i.e., they occur without a triggering cause or “trigger” that is apparent to the patient and are not regularly tied to specific situations – such as driving, department stores, crowds, or elevators.

As a consequence of experiencing intense panic attacks, avoidance behavior often results and those affected restrict their lifestyle, they no longer go to places and situations in which they have experienced these anxiety attacks.

1.6 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The estimated lifetime prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder is 3 %, making obsessive-compulsive disorder the fourth highest psychogenic disorder after depression, anxiety disorders, and dependence disorders. In 75 % of obsessive-compulsive disorder cases, another psychogenic disorder (comorbidity) exists.

Pedantry and compulsiveness are character traits of many people, which in moderation also have advantages – such as being professionally well organized and working in a structured manner. Compulsion in the psychopathological sense, on the other hand, is understood as a very burdensome and suffering pressure generating rigidity. This includes thoughts and/or impulses to act and actions that impose themselves and cannot be suppressed or, if suppressed, lead to considerable anxiety.

Obsessive thoughts are characterized by intrusive and recurrent thoughts, which then often lead to corresponding compulsive impulses and actions. A large proportion of patients suffer from the mixed form, i.e., both obsessive thoughts and compulsive acts. The compulsions – and especially the attempts to suppress the obsessive thoughts and compulsive rituals – are accompanied by significant aversive emotions such as fear and disgust. The best-known obsessive-compulsive disorder is probably the washing compulsion – out of fear of contamination, some sufferers wash their hands (bloody) up to 100 times a day. The control compulsion is also widespread – sufferers return home several times to check whether the coffee machine is switched off and/or the front door is locked. The examples of washing and checking compulsions also illustrate the enormous costs in terms of the time required to “control” the compulsions. De facto, however, people who suffer from an obsessive-compulsive disorder are controlled by their compulsions and are thus extremely influenced in their way of life, freedom and quality of life.

Obsessive-compulsive disorders, which cause high levels of distress, require psychiatric and/or psychological-therapeutic treatment, as untreated cases are at high risk of becoming chronic.

-

Prevalence of anxiety disorders

There are different prevalence rates for the forms of anxiety disorders presented above. The lifetime prevalence for one form of anxiety disorder is estimated at 30 %, which means that every third person suffers from an anxiety disorder once in their lifetime. This makes anxiety disorders – along with depression – one of the most common psychogenic diseases or stresses.

-

Causes of anxiety disorders

As with depression, the causes of anxiety disorders are multifactorial and biopsychosocial in nature; this means that the cause of an anxiety disorder is a combination of biological and psychosocial factors. The diathesis-stress model also applies here. Thus, the likelihood of onset of an anxiety disorder increases when individuals with a disposition or predisposition to anxiety are simultaneously exposed to prolonged and increased stress.

Evidence for the influence of biological factors is provided by numerous empirical studies of monozygotic twins, which show that relatives of persons with an anxiety disorder have a two- to threefold increased risk of also developing an anxiety disorder. Anxiety patients show a hypersensitivity and overreaction in certain brain areas, especially in the amygdala and the limbic system, which subsequently influences cognitive processes in a dysfunctional way. Messenger or neurotransmitter systems – such as norepinephrine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) – play a crucial role in this process. The drug and short-term (!) treatment of acute anxiety disorders with benzodiazepines targets the GABA receptors – short-term because benzodiazepines carry a high risk of dependence! The dysfunctional processes show a parallel to those in depression: whereas depressed people selectively focus on negative aspects and events, anxiety patients focus on potential dangers. Potentially ambivalent stimuli are often quickly interpreted as dangerous.

In addition to the possible biological factors, psychogenic and psychosocial factors play a very significant role in anxiety disorders, similar to depression, only the most important of which are outlined here. Other psychosocial factors will be discussed in more detail in the following section on the treatment and therapy of anxiety disorders.

Learning theory in the sense of classical (and operant) conditioning is especially important in phobias – just as they were learned, they can be unlearned. The learning theory in the sense of model learning emphasizes unfavorable early childhood experiences and developmental deficits, traumatic life events, overprotective parenting style and the way parents or close caregivers deal with fears, anxieties and worries, from which corresponding anxiety disorders or disturbance patterns can result.

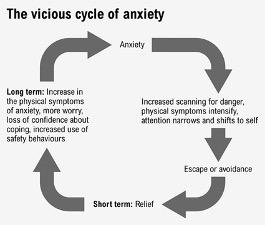

The “fear of fear” experienced by anxiety patients is represented by the circular model of anxiety. The chain of effects looks simplified as follows: Triggers of the fear reaction are thoughts and/or physical changes in the sense of misperceptions such as an accelerated, often irregular pulse or a lumpy feeling in the throat. The thoughts and physical discomfort lead to (further) thoughts of “danger”, which subsequently increases the fear and then again the intensity of the autonomic discomfort. The figure below shows the circular model of anxiety in simplified form.

Simplified circuit model of anxiety

Common to the majority of anxiety disorders is a strong avoidance behavior as a defense mechanism against the supposedly dangerous places, objects, situations or encounters – although this reinforces the anxiety. This avoidance behavior is not only a key element in maintaining the anxiety, but also increases the intensity of the psychological and physical anxiety symptoms. Thus, the (gradual) unlearning of the avoidance behavior – or even its rapid breaking through in the form of flooding – plays a central role in the treatment and therapy approaches discussed below.

-

Treatment and therapy for anxiety disorders

A number of evidence-based and effective treatment options exist for anxiety disorders. After initial diagnostic assessment, the appropriate multimodal therapy is derived and a treatment plan is developed for the patient. This is reviewed for its effectiveness as the therapy progresses and, if appropriate, modified.

4.1. Biological therapy methods for the treatment of anxiety disorders

Biological treatment approaches fall into the psychiatric field and include treatment with psychoactive medication, especially antidepressants. Most notable are selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRI/SNRI), which prolong the availability of serotonin and/or norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft and are considered to be relatively well tolerated with a favorable side effect profile. Antidepressants, originally developed for the pharmacological treatment of depression, are now also increasingly used to treat anxiety disorders.

If pronounced sleep disturbances, agitation, an acute crisis situation or suicidal tendencies are present, benzodiazepines (tranquilizers) may be indicated for short-term (!) drug intervention – short-term because these drugs have a great addictive potential with complications on discontinuation in the form of anxiety-increasing withdrawal symptoms! Furthermore, sedating drugs undermine the examination of possible causes of anxiety as well as the development and implementation of solution-oriented interventions.

Pharmacotherapy alone is not recommended – it should always be complemented by psychotherapeutic treatments.

As with depression, exercise can be considered as an absolutely side-effect-free “biological self-therapy” for anxiety disorders. Moderate endurance exercise leads to a mood-improving and anxiety-reducing release of endorphins (self-produced, endogenous morphine). Furthermore, physical endurance exercise also increases body awareness and confidence in physical resilience. If you then also practice sports with sociability – such as team sports, tennis or dancing – this also includes the possibility of positive social contacts and thus represents an important psychosocial measure.

4.2. Relaxation and meditation techniques for the treatment of anxiety disorders.

Stress- and anxiety-reducing relaxation procedures and mindfulness-based meditation techniques are relatively easy to learn and can then be applied independently in everyday life at the first signs of anxiety and tension for rapid relaxation. Longer-term and regular use of relaxation and/or meditation techniques brings health-promoting physiological and psychological effects, which in particular make it easier to deal with stress and (thus) also bring about an effective reduction in vegetative complaints in anxiety disorders. The physiological effects include activation of the parasympathetic nervous system: there is a slowing down and regularity of breathing, reduction of heart rate and arterial blood pressure, as well as tonus reduction of skeletal muscles. Psychological effects include an increase in composure and mood.

Autogenic training and progressive muscle relaxation represent the most efficient relaxation methods.

In recent years, mindfulness-based meditation methods have become established, the regular use of which represents a – at least supportive – method for many sufferers to better deal with and reduce states of anxiety and tension.

By mindfulness we mean a specific process of attention which is intentional, focused on the present moment, and above all non-judgmental. Mindfulness means to be in the present moment – in the here and now – to be aware, to be attentive, and not to judge or evaluate. Mindfulness is a technique that can be trained and even more an attitude that can be learned. Mindfulness serves the acceptance – so important at first – of the anxiety problem, which can then lead to a more relaxed way of dealing with the anxiety while at the same time increasing the readiness for therapy.

With longer-term practice of the meditation technique – initially under psychological guidance – (such as sitting and breathing meditations or body scan), the following beneficial effects on the vegetative system are described by anxiety patients:

- slowing and increased regularity of breathing,

- decrease in heart rate,

- decrease in arterial blood pressure.

Elements of the outlined mindfulness have for some time also found their way into the cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders outlined below.

4.3 Cognitive behavioral therapy for the effective treatment of anxiety disorders.

Treatments based on the principles of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have been shown to be particularly effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders, as in the treatment of depression. Cognitive-behavioral therapy includes efficient and relieving methods that aim at changing thought and perception processes in order to positively influence feelings (emotions) and subsequently behavior.

With regard to anxiety disorders, CBT includes the following techniques, among others, which patients can apply independently as therapy progresses:

- De-catastrophizing: Questioning the subjective evaluation of a situation, encounter, or challenge: “Would it really be a disaster if the feared situation were to occur?”

- Reality testing: fears and worries are tested for their reality content; for this purpose, the patient is encouraged to collect evidence in everyday life that speaks for or against the hypotheses that trigger and maintain the anxiety and fear.

- Behavior change: Behaviors that maintain the stress are identified and replaced step by step with anxiety-reducing and well-being-enhancing behaviors and alternatives. For example, the widespread tendencies to fruitless brooding and worry chains can be stopped and sustainably reduced. Subsequently, the avoidance behavior characteristic of anxiety disorders can be gradually decreased by confronting the anxiety-provoking situations and encounters, which has a liberating effect on patients.

- Mindfulness: The regular application of the technique and the learnable attitude leads to an efficient reduction of stress reactivity and to an increased acceptance, which leads to a more mindful handling of ourselves and our fears.

Two more special procedures within CBT are explained below: exposure and confrontation techniques – for the treatment of phobias – and exposure with response prevention for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

4.3.1 Desensitization, exposure and confrontation techniques.

The special CBT techniques of systematic desensitization followed by exposure and confrontation are used especially with phobias. The following example of an acquired elevator phobia will show how a conditioned phobia can be unlearned through confrontation and exposure therapy. For the majority of affected persons this leads to a noticeably reduced symptomatology when they get into the feared “phobic situation”.

Important note: The following example is simplified and a medical clarification of the (cardiovascular) resilience should always be performed before a psychological exposure and confrontation therapy!

Case study on exposure and confrontation therapy:

Our 35-year-old client, Mr. K. from Vienna, is married in a happy marriage, has neither health nor financial or professional problems, and has a good circle of friends. These favorable conditions contribute to his psychological stability. Mr. K. works in field service, which usually requires business trips lasting several days. On a business trip to Graz, he experiences a power failure of about one hour while riding the elevator in the hotel there. He gets stuck in the elevator on the way to the underground parking garage between the first and second basement levels. The emergency call system in the elevator does not work; moreover, he has no cell phone reception in the well-insulated elevator. After some time, Mr. K. is overcome by an increasingly oppressive feeling – with his pulse rising and sweating. Also, the questioning thought shoots through his head; “What can I do if a fire should break out in the hotel now?” Over the next half hour, the physical and mental trepidation and discomfort become even more intense. Before the power is restored and Mr. K. can leave the elevator, he has suffered a violent panic attack.

Subsequently, our client tries – whenever possible – to avoid riding the elevator – in particular, he avoids riding alone in the elevator. This avoidance solidifies his anticipatory anxiety whenever he has to use elevators.

Mr. K. ultimately seeks psychological advice and support from therapist T. She first explains to him that he has acquired a phobia of elevators as a result of what he has experienced. In the first session, Mr. K. is taught relaxation techniques. Then he mentally goes through the situation of riding in an elevator in an imagination exercise: From just imagining riding the elevator, to getting into the elevator, to the tense ride, to – unlikely but possible – getting stuck again. As part of this systematic desensitization, Ms. T. teaches him how to use the relaxation and breathing techniques he has learned at the same time.

In the next session, Mr. K. is prepared by his therapist to ride an elevator in a Viennese high-rise building for a longer period of time, first with her and then alone. He would again experience the somatic and psychological stress and anxiety symptoms, but these would gradually diminish with prolonged exposure to the elevator ride.

In the following week, Mr. K exposed and confronted himself with elevator riding. During the first rides together with the therapist, the complaints were still within limits. However, during the initial ride alone, the experienced anxiety symptoms return with great intensity. After some time of uninterrupted elevator riding, however, her K. feels that the fear, anxiety feelings and physical symptoms gradually decrease again noticeably on their own.

Crucial for Mr. K. was the exposure to and confrontation with elevator use and this until the peak of anxiety and its physical symptoms was reached and exceeded. Prior to the psychological intervention described, Mr. K. – when using an elevator could not be avoided – always left the anxiety-producing elevators as quickly as possible, i.e., at times when the anxiety was still on the rise. By doing so, however, he never reached and experienced the maximum of his anxiety and thus, above all, the decisive abatement of anxiety with its physical and psychological symptoms. Only by exposing himself to the peak of anxiety could he experience and feel that the anxiety would gradually subside again after passing through its maximum and that he could break the vicious circle of “fear of fear”.

The presented principles of desensitization with subsequent exposure and confrontation can be applied accordingly and effectively to all phobias – e.g. animal phobias, but also social phobia.

4.3.2 Exposure with reaction prevention

The cognitive-behavioral treatment of exposure with response prevention shows high effectiveness in the therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder, which will be explained by the example of compulsive washing. The fear of contamination of the affected persons results in very high tension if they cannot follow their compulsive washing ritual. However, washing then always causes only a very short-term reduction in anxiety and tension. In an exposure treatment, a patient suffering from washing compulsion is exposed to a confrontation with the compulsive stimuli: he is instructed to touch dirty objects in the presence of the therapist and to endure the anxiety for a longer period of time without giving in to the washing impulse. Through this response management in the form of response prevention (refraining from washing), the patient experiences that his anxiety and tension gradually diminish over time.

It is crucial for the success of the therapy that he transfers this exposure with reaction prevention into his living space, i.e. that he exposes himself to the omission of the washing impulse alone at home for several hours. Thus, as time progresses, the anxiety and tension of not following the washing compulsion will gradually reduce more and more.

-

Summary and résumé

Anxiety disorders represent one of the most common psychological distress conditions or illnesses. With a prevalence rate of up to 30 %, one in three people experience some form of anxiety disorder once in their lifetime. There is much evidence to suggest that the diverse professional and private demands of adaptation and the rapidly changing social structures of our fast-paced times favor the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders. The symptoms of anxiety disorders are of a physical (vegetative) and psychological nature with the leading symptoms of high tension and anxiety.

The main anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and phobias; obsessive-compulsive disorder is also associated with anxiety symptoms.

With regard to the causes, as with depression and most other psychogenic stress states or disorders, these are multifactorial and include biological, psychosocial, and also life history components. An important factor in almost all anxiety disorders represents the marked avoidance behavior that perpetuates the anxiety disorder.

There are a number of effective psychological and psychotherapeutic treatment approaches, with cognitive behavioral therapy in particular having proven to be an effective stress-reducing treatment option, in addition to psychological-physiological relaxation techniques and mindfulness-based meditation techniques. Cognitive behavioral therapy helps many patients to gradually reduce and ultimately break through their counterproductive avoidance behaviors.

Thus, people suffering from an anxiety disorder are provided with a stress-reducing way of dealing with their fears and paths to salutogenesis, which contribute to increasing emotional stabilization and thus to regaining life satisfaction and quality of life.

Anxiety disorders often occur together with depression (comorbidity).

Dealing with and therapy of depression